The Dvar/article below is also available as a Podcast, simply click any of the following options: Apple, Spotify, Bandcamp, Soundcloud, &/or Youtube.

________________________________________________________

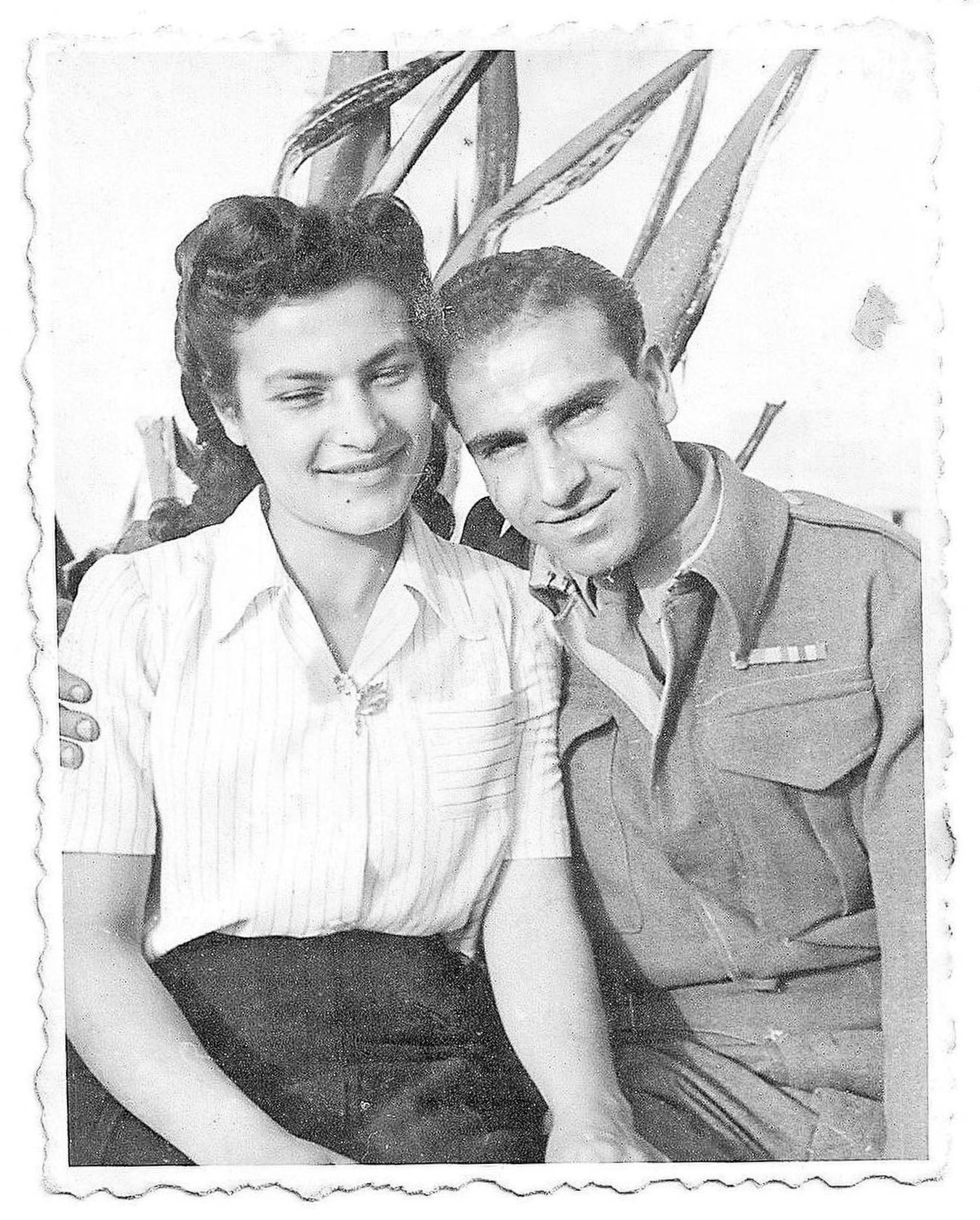

There was a time when I stopped visiting Israel, because it was too difficult for me to go there after my Savta passed away. Her house had always been my first stop; I would run there directly from Ben Gurion airport. She would likely have some Yemenite food and mind-blowing schnitzel awaiting my arrival. Back when I was in Yeshiva and lived in Yerushalayim, I would take my friends from yeshiva to my Savta’s in Ramat Gan for Shabbatot (they all called her G-ma;). I remember her waking up at 5 am every day, covering her head and saying the morning tefillah. She would cook Yemenite food and Moroccan salads, and my friends and I would sing Shabbat songs in Hebrew, as she sat on the couch crying from happiness. It’s incredible to realize all the time that she and her family were exiled in Yemen and Ethiopia, and that they were able to come back to Israel, and that she could see her grandson living in Yerushalayim, singing the songs that have been sung throughout history every Shabbat since the Jews left Egypt. She had made it, we had made it — the yearning for home and the unification of a people with its ancestral homeland had been realized in her lifetime.

Yemenite Jews are unique in that they are our strongest link to the Beit HaMikdash (Holy Temple). They settled in Yemen while the Temple still stood and have maintained their Hebrew pronunciations and Jewish practices in a completely unique way. Whereas most every other Jewish tribe has traveled and assimilated into the larger cultures around them, Yemenite Jews have stayed in Yemen up until the last hundred or so years. Even the great Eastern European Gadol V’Posek HaDor Rav Moshe Feinstein said that the Yemenite Jews pronunciation of Hebrew is closest to that of Moses, Moshe Rabbeinu.

Concepts in Kabbalah

Now to the Parashah, which centers around the Beit HaMikdash and its practices and how these pertain to our lives.

The Hebrew word kabbalah means “parallel” or “correspondence.” So Kabbalah is the mystical teaching of the parallels and correspondences between all of creation and the Divine power that creates it. The structures of the four letters of the Divine Name (Havayah) express the Divine creative force that sustains and is manifested in all levels of reality. We explored this notion in Vayakhel’s dvar, when we spoke about the parallels between Hashem’s “arousal from above” and our “arousal from below.”

This was illustrated two millennia ago in the sacrificial rituals of the Beit HaMikdash. The Temple is a microcosm of the creation and all the rituals performed in it are both symbolic of and actualizations of the Divine service each of us is tasked with in the physical world.

The Arizal explains that Hashem created five kingdoms in our physical world: the “silent” i.e. inanimate or mineral, the vegetable, the animal, the “articulate” i.e. man, and, finally, the soul. Each of these is a world unto itself, and each is also a projection of the one that precedes it at a lower spiritual level. This structure of the physical world reflects the structure of the highest spiritual realm, the atzilut, a realm of pure “emanation”.

In the process of creating all of the worlds below atzilut, a shattering happened. Out of tohu, “chaos”, came Divine sparks which infused themselves within all aspects of reality in all the lower worlds, including the lowest, which is our physical world. And the Kabbalah explains the other fundamental aspect of the creation of the world– tikkun, meaning “rectification” or “repair”. When we use any element of our physical world for a Divine purpose, we elevate the spark within it to its holy source, turning the physical back into the spiritual.1

Soul’s Sacrifice of the Animal Within

Now that we have a bit of the kabbalistic background, we can jump into the actual words in this week’s parashah, Vayikra. The portion begins: “When one among you offers a sacrifice to G-d…”.2 Immediately, we ask, what sort of sacrifice? Why? And how? King David, whose son built the first Temple, writes in Psalms, “For You [G-d] do not desire sacrifices; else I would give it: You do not delight in burnt offering. The sacrifice of God is a broken spirit. A broken and contrite heart, O God, You will not despise.”3 Animal sacrifices were a way for ancient Jews to elevate themselves spiritually, but the sacrifices would have been meaningless if they weren’t done with true intention and a full heart to heal oneself and the harms one has done. King David writes that God will not despise a “broken spirit”, because true remorse makes a person feel broken, and true repentance comes from the desire to be connected to Hashem again, in order to be whole. In order to achieve this level of return, teshuva, we were commanded to bring a sacrifice in the time of the Temple, just as we are now commanded to pray, in the absence of the Temple.

The Hebrew word for sacrifice is korban which comes from the word karov or lekarev meaning “close” or “to bring closer”. It’s written in the pasuk, מִכֶּם, which means yourself, implying the one who is offering the korban, is sacrificing themself. I love how Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks puts it:

Vayikra is about why love needs law and law needs love. It is about the quotidian acts of devotion that bring two beings close, even when one of them is vaster than the universe and the other is a mortal of flesh and blood. It is about being human, sinning, falling short, always conscious of our fragile hold on life, yet seeking to come close to God and – what is sometimes harder – allowing Him to come close to us.4

Last week, we discussed Hashem’s dwelling in the sanctuary representing His deeper dwelling amongst each and every one of us. This week, the Torah teaches how the holy priests are guided in their service and sacrifice in the sanctuary of the past.

The korbanot are a beautiful and spiritual ritual – picture the elements surrounding the sacrifice, with the presence of the kohanim (priests) accompanied by the chanting and songs of the levi’im, the (Levites). The Zohar teaches that the service of the kohanim was in silence, with the devotion of the heart, signifying hamshachah (drawing forth, from Above), while the service of the levi’im was with song and music, signifying hala’ah (sublimation; elevating from below upwards).5 As it’s written, “The Kohanim in their silent service and their desire drew [G-d’s presence] downwards and the Levites in their songs and praises drew [man’s soul and his sacrifice] upwards.”6 This is mirrored in how we tend to the sanctuaries within our own souls, the inner acts of sacrifice we practice each day, the desire we have to bring holiness down from above, and the artfulness we use to draw our spirits and surroundings upward.

Vayikra lists a variety of korbanot (sacrifices) to be brought by the individual and the community. Below are some general categories:

Olah (burnt offering, עלה) – an animal sacrifice that is completely burnt upon the altar.

Minchah (meal-offering, מנחה) – an offering a fine flower, oil, and frankincense

Shelamim (peace-offering, שלמים) – a fire-offering of the fats and kidneys of an animal; the other parts are given to the Kohen, and the remainder is eaten by the owner.

Chatat (sin-offering, חטאת) – the blood of the animal is poured upon the Altar and the fats are also burnt; the rest is eaten by the Kohanim.

Asham (guilt-offering, אשם) – depending on the individual’s means, this offering may be either an animal from the flock, two doves, or fine flour.

Milu’im (inauguration-offering, מלואים) – an offering brought by a Kohen when he joins the service in the Bait HaMikdash.

Korban Todah (thanksgiving-offering, קרבן תודה) – an animal sacrifice brought together with four different types of bread; some parts of the animals are burnt upon the Altar, others are given to the Kohen, and the remainder is eaten by the owner.

Korban tamid (daily sacrifice, קרבן תמיד) – every morning and afternoon, the Kohanim in the Mishkan-Tabernacle (and later in the Bait HaMikdash) brought a fire-offering of a yearling lamb together with fine flour and oil.

Ketoret (incense-offering, קטרת) – an offering of eleven finely ground spices, which were burnt upon the Golden Altar in the Inner Sanctuary, next to the Holy of Holies.7

There are two concrete ways in which we could, to some extent, simulate bringing a korban. In Talmud Menachot it teaches, based on ‘This is the law of the sin offering’,8 that anyone who engages in studying the law of the sin offering is ascribed credit as though he sacrificed a sin offering.9 Aside from learning the laws, there is a custom to recite פרשת הקרבנות (parashat hakorbanot) as part of our daily tefillah, specifically saying:

אם נתחיבתי חטאת, שתהא אמירה זו מרצה לפניך כאלו הקרבתי חטאת

– “If I am obliged to bring a sin-offering (or any other korban), may it be Your Will that the recitation of the portion dealing with חטאת should be considered as if I brought the sin-offering.”

Of Yourself with Love

The Alter Rebbe breaks down the pasuk – ‘אָדָ֗ם ‘כִּֽי־יַקְרִ֥יב מִכֶּ֛ם קׇרְבָּ֖ן לַֽה – Adam ki yakriv – “If a man desires to draw close to Divinity, then mikem korban laHashem,10 you must offer of yourself.” The word mikem signifies the offering of the nefesh elokit (our Divine soul) and, further in the pasuk, the phrase “of the animals..” signifies the “animal’ in man’s heart (the nefesh habahamit – the animal soul) – from the animal within, one’s base characteristics. The Lubavitcher Rebbe expounds on this lesson, explaining that the ultimate purpose for man is not an avodah (service) relating to the Divine soul, for its own sake, but rather to achieve a birur, a refinement of the animal soul which we see in the word mikem (of you) followed by korban leHashem (an offering to God). We see in the sentence, “If any man brings an offering of you…”: to draw close to God, one must make a sacrifice of “you”, of oneself. So, “you” is the essential element of a holy sacrifice– from the heart, from one’s godly soul, turning good intention into good action.

The intention of the words ‘from the heart’, means that the person has to bring the sacrifice willingly. It is the same with tefillah (prayer), we should pray out of Love not obligation. The same applies with lending money and other matters “between man and his fellow man,” which are meant to be performed willingly and b’simchah (with joy). The Bartinura comments on Talmud Avot regarding giving tzedakah (charity): if someone were to do it with their “face pressed to the ground” (under duress), it would be as though the person didn’t give the tzedakah at all. The person will still receive a reward for the mitzvah, but, in a sense, it is as though the person didn’t perform the mitzvah because they did it purely out of obligation instead of willingly and lovingly.11

The second part of the pasuk (verse) and sacrifice pertains to an animal and one’s animal soul. As it’s written, “…from animals – from cattle or from the flock shall you bring your offering.”12 This relates to the physical body, physical desires, the natural world, so it is the physical sacrifice– actually giving up the animal (or its modern equivalent)– with the purpose to sanctify and redirect the “animal” in man. The Rebbe explains that when the animal in man is harnessed in the service of God it has the power to take him closer to God than his Godly soul alone could reach. The greater the sacrifice, the greater the reward.

Reb Natan of Breslov teaches that a peron’s sin is due to their lack of da’at as it’s written, “A person sins only because a spirit of foolishness overcame him.”13 To rectify this lack of da’at the person must bring an animal sacrifice which reflects that animals lack da’at and in this way the person demonstrates their readiness to sacrifice their animalistic tendencies.14 We learn that the animal sacrifices in particular have the power to rectify the lowest worlds15 and that the korbanot in general correspond to the Act of Creation, when Hashem separated good from “bad”. In the same way the korbanot separate good from evil.16

The Three Soul-Garments

The same way that any animal that is to be a korban cannot have a blemish, we are tasked with not having a blemish in regards to the “animal” within ourselves. This is done through self-examination and true remorse, searching one’s soul for rifts in the unity of one’s being; this includes the three soul-garments of thought, speech and deed. If a kosher animal was torn apart by a predator, it would then be deemed unkosher, “treif”, which literally means “torn”. Unlike an animal deemed treif, however, we are able to do full repentance, which in Hebrew is called teshuva, meaning “to return”, so we never have to become completely torn away from G-d. This Parashah teaches us the process of taking the Sitra Achra, the fallen sparks, and elevating them into light, supplementing the darkness. But this can only be done through both of our inclinations, for good and for evil. This is the meaning of the famous passage, “And you shall love the Eternal, your God, with all your heart.”17 Our most profound sacrifice is when we subdue and harness the overwhelming power of the evil inclination and manage to use that energy for good, for Hashem.

The Zohar states this clearly, “When the Sitra Achra are subdued below [in our lower world], the Holy One, blessed be He, is exalted above and is aggrandized in His glory. In fact, there is no worship of God except when it issues forth from darkness, and no good except when it proceeds from evil… The perfection of all things is attained when the intermingled good and evil become totally good, for there is no good except if it issues out of evil. By that good His glory rises, and that is the perfect worship.”18

This is seen in the “Parable of the Harlot” in which a king instructed his son to lead an exemplary and moral life and not to fall into temptation. Meanwhile, the king secretly tasked a temptress to seduce his son, testing his son’s devotion to him. The woman tried everything to seduce the prince, but he rejected all attempts. At this, his father, the king, rejoiced and bestowed all his honor and greatest gifts to his son, the prince. The Zohar means to illustrate that all the glory due to the prince was brought about by the temptress! “Surely she is to be praised on all accounts, for, firstly, she fulfilled the king’s command and secondly, she caused the son to receive all that good and led to that intense love of the king for his son.” 19 Conquering the evil within ourselves demonstrates our truest devotion to Hashem.

As you read through the Parashah, you will notice that the sacrifices are meant to create “… an aroma that is pleasing to G-d.” Not only must each person bring the sacrifice to Hashem with a full heart, but each slaughtered animal must be “fit” to be sacrificed, so that it is pleasing to Hashem. As above, so below: when preparing and shechting an animal for us to eat, the animal must be fit, i.e. kosher. The Jewish laws and rituals for this are very specific and strict, and even after the animal is slaughtered properly and in a humane way, it is still inspected to see that there are no fatal lesions on the lungs. These are all aspects of the animal being “fit” or kosher. In regards to us being “fit”, we must eat as a means to serve Hashem, being mindful of that as its purpose. When our food is elevated into holiness, then the life it came from and our lives are elevated. So, our sages teach that “man’s table is like an altar”. This is why on Shabbat we salt the challah, just as the sacrifices were salted. Shabbat is a taste of the world to come, prayer is a taste and a mirroring of the rituals we once carried out in the Temple.

But if we have intention without action, or action without heart, then the “aroma” we create is not pleasing and the sparks are not fully elevated. My prayer and blessing is that we mirror the upper realms in this physical world, that we liberate and elevate all the fallen sparks, so that the world can reach its maximal spiritual potential that is pleasing on the highest level to ourselves and Hashem so much so that the final redemption reveals itself speedily.

Please note: You can read the full and final version of this Dvar/Article in my third book, ‘LIGHT OF THE INFINITE: THE SOUND OF ILLUMINATION.’

info: The book parallels the parshiot (weekly Torah reading) of Vayikra/Leviticus, which we are reading now! I act as your spiritual DJ, curating mystical insights and how to live in love by expounding on the infinite light of Kabbalah radiating through the Torah.

Just like on the dance floor, where the right song at the right moment can elevate our physical being, this book hits all the right beats for our spiritual being.

We cannot choose our blessings or how much light we will receive, but we can continually work to craft ourselves into vessels that are open to receiving – and giving – blessings of light.

All five books in the series, titled, The Genesis of Light, The Exodus of Darkness, The Sound of Illumination,Transformation in the Desert of Darkness, and Emanations of Illumination are available now at Amazon, and Barnes and Noble.

Amazon prime link – – https://amzn.to/3uvdfxw

Notes & Sources

- Apples from the Orchard, The Arizal, p. 519

- Leviticus 1:2

- Psalms 51:18,19

- Covenant & Conversation: Leviticus by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, p. 5

- Zohar III:39a

- Ibid Part II, 239a; Part III, 26b

- Rebbe Nachman’s Torah, compiled by Chaim Kramer, p. 303

- Leviticus 6:18

- Menachot 110a:13

- Leviticus 1:2

- Darash Moshe, p. 168

- Leviticus 1:2

- Talmud Sotah 3a

- Ibid I, pp. 39a, 78

- Ibid I, p. 163a

- Likutey Halachot I, p. 3a

- Deuteronomy 6:5

- Zohar II:184a

- Ibid II:163a