The Dvar/article below is also available as a Podcast, simply click any of the following options: Apple, Spotify, Bandcamp, Soundcloud, &/or Youtube.

_____________________________________________________________

The majority of us have the best of intentions, but life sometimes gets in the way. Even when we fully promise and believe that we are going to help a friend out, there are times that, in the end, it doesn’t work out how we had hoped. It’s these promises said with such love and enthusiasm that give us hope and make us feel that we aren’t alone. The flip side is when empty promises leave us feeling misled, helpless, or stranded. People shouldn’t commit to things they don’t actually have time for. Language is powerful. Indeed, as we covered three parshiot ago in Chukat, we learn from Hashem that words create worlds. In the beginning, Hashem spoke existence into being. It is the same with each of us, speech is a way to connect and create or to disconnect and destroy.

Thinking about nedarim (vows) in this parashah brought to mind a song from my favorite band, The Beastie Boys, dubbed, “Don’t Play No Games That I Can’t Win,” featuring Santigold. It’s one of the main singles off their album, Hot Sauce Committee Part Two. (They never intended to make a Part One. Maybe any piece of art that’s actually released is actually Part Two, as Part One is only known to its creator.) The song title came to mind because I was thinking about how often people say that they will do things “bli neder”, in other words, without a strict vow. It’s a way for people to say “I do intend to do this, but without the weight of a vow”. It’s a way to play the game and ensure that you never lose.

The verse that opens our double parashah of Matot-Massei reads as such:

וַיְדַבֵּ֤ר מֹשֶׁה֙ אֶל־רָאשֵׁ֣י הַמַּטּ֔וֹת לִבְנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל לֵאמֹ֑ר זֶ֣ה הַדָּבָ֔ר אֲשֶׁ֖ר צִוָּ֥ה ה’׃ אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי־יִדֹּ֨ר נֶ֜דֶר לַֽה’ אֽוֹ־הִשָּׁ֤בַע שְׁבֻעָה֙ לֶאְסֹ֤ר אִסָּר֙ עַל־נַפְשׁ֔וֹ לֹ֥א יַחֵ֖ל דְּבָר֑וֹ כְּכָל־הַיֹּצֵ֥א־הַיֹּצֵ֥א מִפִּ֖יו יַעֲשֶֽׂה

Moshe spoke to the tribal heads of the Israelites, telling them that this is the word that God had commanded: If a man makes a vow to God, or makes an oath to obligate himself, he must not break his word. He must do all that he expressed verbally.1

If you’ve heard someone say “bli neder” after agreeing to do something, it comes from this very verse. When it says “He must not break his word,” this creates what’s called a negative commandment. It’s a prohibition against not following through on what you commit to.

The word neder (נדר) means “vow”, and over time, the word has come to mean all types of oaths and vows. But there is a halachic distinction between a neder (vow) and a shevuah (oath). A neder creates an obligation with respect to objects, whereas a shevuah creates an obligation only with respect to the person who makes it. So if a person makes an oath that he will not do a specific mitzvah, e.g. sitting in a sukkah, the oath does not exempt him from the duty to perform that mitzvah. This is because we’ve already vowed at Mount Sinai to perform all of the mitzvot. Such an oath is therefore meaningless– a shevuat shav. But a person can make a neder, a vow, to not sit in a sukkah, which applies to the sukkah rather than to himself.2

A typical neder or shevuah invokes God’s name. Though there is a concept of yadot nedarim, “extensions of vows,” which means that even if you exclude God’s name, it’s still considered a vow. Taking that even further, there is a notion of kinuyei nedarim (“idioms of vows”), meaning that even if you promise or commit to do something, or use any similar language to a vow or oath, it is as if you are accepting the full legal commitment. This brings to mind the phrase ‘my word is my bond.’ The phrase dates back to merchant traders in the late 1500s, who, before the custom of written pledges developed, would have verbal agreements and use that phrase as legally binding.

With that said, when someone says, “I will do X, bli neder,” that person is saying, “I am not making a vow, but I will try to do X.” People say it so often because swearing or making an oath is considered very serious, so much so that the prohibition of making a false or even a needless oath is one of the top Ten Commandments, just after the commandment not to serve idols. The bli neder doesn’t take away the responsibility of what the person agreed to do, but it does take care of the prohibitions regarding making and keeping vows. The focus is still on the obligation as stated, “According to whatever came out of his mouth, he shall do.” (Numbers 30:3) This is all to be sure people follow through with their word, as it is human nature to make a pledge in times of trouble and sometime later regret having done so and find excuses not to follow through. As it’s written in Kohelet, “Do not let your mouth make your body sin.”3

Emphasizing vows and oaths as a commandment is meant to shed light on the power each of us has when using speech and choosing words. Inspiring words to a friend or stranger can give them life and light, perhaps inspire them to do the same for others, bringing more love into the world. On the flip side is speaking harsh and negative words of darkness that to many feel like death; they carry the power to take happiness away from a person, inspiration away from an idea and sometimes, in extreme circumstances, they take value and life from a person’s spirit.

Earlier in Bamidbar, (Numbers 6) we read about the Nazir (nazirite), a person who decides to take a vow to live a strict holy lifestyle. If one goes this route, one of the laws is that they are not allowed to drink wine or cut their hair or come into close contact with the dead. To complete their Nazir ritual/term, they bring a sin offering to the Beit HaMikdash (Holy Temple) in Jerusalem. Since the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash, speech through prayers has replaced the sacrifices/offerings.

The concept of Nazir is introduced in the Torah in the following verse, ‘אִ֣ישׁ אֽוֹ־אִשָּׁ֗ה כִּ֤י יַפְלִא֙ לִנְדֹּר֙ נֶ֣דֶר נָזִ֔יר לְהַזִּ֖יר לַֽה4 which translates as, “when either a man or woman shall pronounce a special vow of a Nazir to separate themselves to the Lord…” In connection to the Nazir and the vow, Onkelos writes, יְפָרֵשׁ לְמִדַּר נְדַר נְזִירוּ, translating the word “יְפָרֵשׁ/yefaresh” as ‘to explain’. When a person becomes a Nazir, they must fully understand the weight of what they are taking upon themselves, so they must say aloud what their vow is, in order to make their meaning clear. And the term “יַפְלִ֖א/yafli” is used a few times in the Torah in connection to vows. (e.g. Vayikra 22:21 and Vayikra 27:2) The Hebrew root word is “פלא/palah” like “pele” which means wonder or amazement.

The Ramban5 explains that we learn from this how amazing it is that Hashem will respond to the vows that we make in a time of crisis as a way to deal with our distress. A person dealing with a crisis or extreme stress turns to Hashem and promises to behave in a certain way if Hashem protects them. The first time we see this is in Bereishit (Genesis), when Yaakov makes his neder to Hashem before leaving Eretz Yisrael on his way to Padan Aram.6 What we see through all of this is Hashem’s receptivity to this type of vow. And we need this kind of vow in our lives– it helps us feel hope and manage the stresses of living in this world. More than it being something Hashem needs or a gift to Hashem, the power here is the pele— the amazing wonder is that we can commit ourselves to God and have our vows honored, even though they are made in moments of distress.

During the first Beit HaMikdash (Holy Temple), Hashem’s splendor shone openly. Even during the seventy years in exile, there was still some of that Divine revelation that was seen and felt in certain individuals. But during the Second Beit HaMikdash, prophecy ceased and the Divine splendor became concealed. It is then that Chazal (the Great Sages) ordained a number of fences and restrictions, so that we would be protected from being overcome by darkness.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe taught that the righteous are forbidden to restrict themselves with vows, whereas the wicked are actually duty bound to do so. The righteous can “Observe Who created [these],”7 various elements of the physical world and see the great light in them, connecting and elevating them on high. Chazal state in Talmud Kiddushin in regard to tzaddikim (righteous ones), “What the Torah forbade you to do is enough,” as one who behaves as they should doesn’t need to avoid the permissible. Abstinence and vows are actually meant for people who find themselves preoccupied by the physical world, caught up in the material. Most of us find it easy to get pulled into the physical, away from the spiritual, let alone trying to elevate the material to spiritual. Nedarim/vows are meant as a way to draw closer to the Infinite by making more explicit commitments to abstain from the finite.8

A few more verses into this parashah, the Torah says in regard to a married woman that her husband can confirm or annul her vows: כָּל־נֵ֛דֶר וְכָל־שְׁבֻעַ֥ת אִסָּ֖ר לְעַנֹּ֣ת נָ֑פֶשׁ אִישָׁ֥הּ יְקִימֶ֖נּוּ וְאִישָׁ֥הּ יְפֵרֶֽנּוּ.9 The Zohar states that oaths occur in the Nukva (the female of Z’eir Anpim, Aramiac for the Hebrew word, Nekavah, ‘feminine’, referring to Z’eir Anpim’s bride) of Z’eir Anpin and that vows occur in the supernal Ima (i.e. binah). But, in principle, both occur in the Nukva of Z’eir Anpim.10

R’ Moshe Wisnefsky, in his translation and commentary on The Arizal’s Dvar Torahs writes:

The feminine aspect of the psyche is the drive within us to actualize God’s purpose in creation, making reality into His home. However, this drive must be coupled with an equal drive to escape the mundane reality of this world in favor of the abstract reality of spirituality; this is the male drive within us. The coupling is necessary because, left to itself, the drive to make separate reality into God’s home would have us penetrate further and further into the darkness of materiality, endangering us of being sucked into it as the memory of Divine experiences fades. Therefore, as the sages say, “vows ensure asceticism,”11 meaning that it behooves us all to set boundaries for ourselves as we prepare to venture into the world of materiality in order to conquer it for God‘s purposes. Thus, the Arizal explains this constructive force of vows and oaths with reference to their salutary effect on Nukva, the feminine archetype.12

Tefillah (prayer) informs our high level of speech by using the Hebrew words of the created world. The Hebrew letters and their associated numerical value are our mystical link and the code, in a sense, that connects our physical and finite world to the spiritual world that is infinite. The laws and Kabbalah around speech and the power and meaning behind each word– their roots and permutations and contexts– hold the key to elevating the mundane into the ineffable. As The Arizal teaches, our prayerful words prepare us to venture into the world of materiality in order to conquer it for Hashem’s purposes. We see this through the mystical significance of a true oath, which is a mitzvah (a positive commandment) when done in the name of God, as it’s written, “… and you will swear by His Name.”13

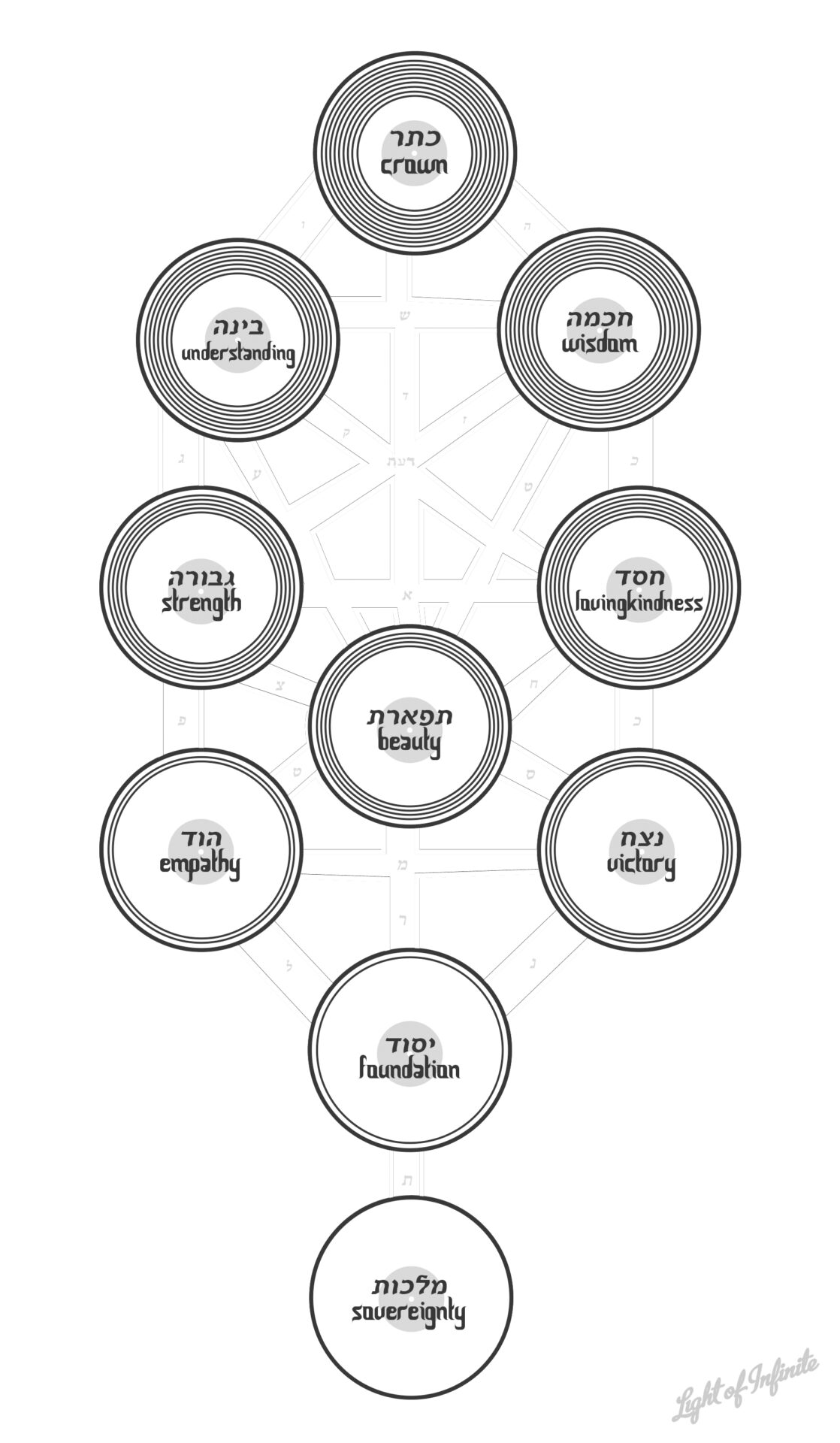

The first letter of the Hebrew Alphabet is א (Aleph). The mystical secrets and all of creation emanate from the letter. The Zohar describes the parts of the Aleph and what they allude to, explaining that the upper point alludes to Keter (crown), which hovers up above Chokhmah (Wisdom) and Binah (Comprehension). The lower point is likened to the chirik (a single vowel sign), which is a single dot (י/yod), corresponding to the earth/Malkhut. The line between the two is the ו/vav, representing the firmament between the two levels, the upper and lower yod. And so, the letter Aleph—its two dots/yods (= 20) and its line/vav (= 6)—has a numerical value of twenty-six, the same as God’s Holy Name YHVH, the Tetragrammaton. The Aleph also encompasses all of the Ten Sefirot: from Keter (Chokhmah and Binah), through the six central Sefirot, to Malkhut. See side graphic for the Sefirot.

Elevating The Mundane To A Spiritual Plane

I sat under the orange tree at the Ben Yehuda home, which I do most every Shabbat. I was talking to David, the head of the house, who grew up on the Carlebach Moshav (Moshav Modi’in) about this double Parashah and the neder that’s addressed in the first pasuk. We spoke about the power of speech that Rebbe Nachman and Reb Natan of Breslov so often discuss, and he broke down that Neder is called Pele and that Pele is Aleph which is Keter. He quoted the verse about the Nazir, ‘אִ֣ישׁ אֽוֹ־אִשָּׁ֗ה כִּ֤י יַפְלִא֙ לִנְדֹּר֙ נֶ֣דֶר נָזִ֔יר לְהַזִּ֖יר לַֽה and explained that if someone took something mutar (allowed) and said, “I am not going to partake of this,” then they go from the 613 commandments that Hashem has commanded to 614 (without breaking the prohibition of adding to the Torah).

And something more kabbalistic and less known is that taking something mutar and making a neder out of it is a way to elevate the mundane. Of course, when we eat food we need to be mindful of why we are eating, what we hope to use the sustenance for, and to say a blessing prior to and after eating the food– all this elevates the food to a spiritual level. Making a neder does the same thing: so if you tell yourself you are making a vow that you are going to eat something or going to do any mundane act that isn’t a positive commandment from the Torah, by making a neder of it, you can turn it into a positive commandment, thus adding to the commandments, at least for that moment. (It should be noted that every person should speak with their Rabbi before making nedarim, as most would suggest not to do so).

All of this is to illustrate that we are all a Torah, in and of ourselves, and that’s why we are able to add to it — and it is a ‘pele’/wonder that we are able to do so. It’s what allows us to take the Neder, that Aleph, and return it to Keter, to its source in the Sefirot. Something that David always stresses when learning any lesson from the Torah is what it means in a person’s life. Yitziat Mitzrayim (the Exodus from Egypt) isn’t only a story that happened to us in the desert thousands of years ago. It’s the story and struggle of our daily lives, and when we internalize each lesson in how we can elevate ourselves, that is when we find our personal redemption, which will usher in a full and final redemption for us all.

Please note: You can read the full and final version of this Dvar in my fourth book, ‘LIGHT OF THE INFINITE: TRANSFORMATION IN THE DESERT OF DARKNESS‘.

info: The book parallels the parshiot (weekly Torah reading) of Bamidbar/Numbers, which we are reading now! I act as your spiritual DJ, curating mystical insights and how to live in love by expounding on the infinite light of Kabbalah radiating through the Torah.

Just like on the dance floor, where the right song at the right moment can elevate our physical being, this book hits all the right beats for our spiritual being.

Four of the five books in the series, titled, The Genesis of Light, The Exodus of Darkness, The Sound of Illumination, and Transformation in the Desert of Darkness are available now at Amazon, and Barnes and Noble. The fifth and final book, Emanations of Illumination, will hit stores on July 11th, 2023.

Amazon prime link – – https://amzn.to/3uvdfxw

** or click to listen on Apple, Spotify,Youtube, or Soundcloud

Save the date: July 11th will be the next global Light of Infinite Festival with Keynote speaker, Rabbi Simon Jacobson, & the release of book # 5 (Emanations of Illumination)!